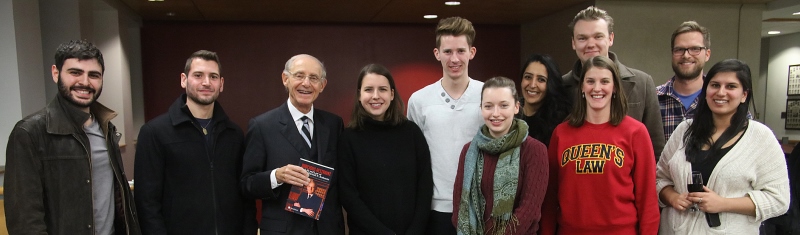

Former Supreme Court Justice Marshall E. Rothstein visited Queen’s on February 9, speaking with students and academics on his nearly 10 years on the bench. The day culminated in a panel discussion on his legal insights, to launch the book Judicious Restraint: The Life and Law of Justice Marshall E. Rothstein.

The book is co-edited by Queen’s own Professor Lisa Kelly and contains a collection of academic papers discussing Rothstein’s contributions to Canadian law. Kelly hosted Rothstein for the day, and students had a chance to meet with him.

“It was an invaluable experience,” says Ivneet Garcha, Law’19. “To learn from the lived experiences of someone who has been so integrally engaged in setting important precedent, and whose approach to advancing law creates an opportunity to reflect on the tensions between law and society, the courts and Parliament, was riveting.”

As a student in Kelly’s class, Garcha was able to hear Rothstein speak informally with students and field their questions. “His humility spoke volumes and was amplified by his quick wit and great sense of humour,” and he was “refreshingly honest, personable, and approachable,” she says.

Rothstein shared personal anecdotes from his time on the Court from 2006 to 2015, as well as his knowledge of how the Court works behind the scenes.

“It was quite impressive how he could negotiate the delicate balance between the aura of a former Supreme Court Justice and the down-to-earth lawyer eager to impart his personal reflections and knowledge to Queen’s Law students,” Garcha says.

Rothstein spent the day at Queen’s before attending the talk in the evening. Not one to steal the spotlight, he listened while the three panelists discussed their contributions to the book, adding in commentary. The panelists were Professor Kelly, Daniel Rosenbluth, Law’15, and Michael Fenrick, both lawyers at Paliare Roland LLP. All three were authors of articles within the collection.

“It’s a highly academic book, dealing with deep legal theory,” Rothstein said.

Dean Bill Flanagan, moderator, jokingly referred to the panel as a roast.

Rosenbluth’s co-authored paper examines the legacy of Rothstein’s administrative law decisions, specifically his contributions to the law in his concurring reasons in the 2009 case Canada v Khosa. “These reasons set out some big ideas in administrative law that we picked up on,” Rosenbluth said.

His article explores Rothstein’s idea that the tension between the rule of law and legislative supremacy only ever arises in the presence of a privative clause. A privative clause is one which specifically shields decisions of an administrative body from being appealed to or reviewed by a court.

Rothstein called the paper insightful and said he wished he had read it before writing his reasons in Khosa. “I lost Khosa, Rothstein said. “I said ‘fine, I’ll live with that.’ But I’ll live with it with a vengeance!”

Fenrick spoke on Rothstein’s ideas about judicial deference to the legislature in the context of freedom of association, zeroing in on his concurring reasons in recent freedom of association decisions, which made the case that courts need to provide the legislature with a sufficient amount of deference to craft solutions for complex labour relations questions.

“The law clerks I disagreed with the most were the ones who were my best law clerks,” said Rothstein.

Fenrick and Kelly were co-clerks for Rothstein.

Kelly spoke about ideology in Canadian legal thought. She challenged the neutrality thesis: the idea that the legal work of judges is inherently separate and distinct from the political work of legislatures. Judges are tasked with providing legally correct and certain answers to questions that often involve open-textured provisions and carry significant distributive consequences. Kelly argued that judges experience a “role tension” as a result of this gap between the ideal of legal certainty and correctness and the practice of making high-stakes decisions.

In order to relieve this tension, she argued that judges may suggest that their opponent’s flawed reasoning is the product of ideological influence, while the judge’s own correct legal reasoning is ideologically pure.

“I don’t think it’s out of a sense of bad faith, nor do I think they are naïve. Rather I think they do it because we all require this of them and they come to expect it of themselves,” she said. Judges are essentially forced to mask ideological commitments in their legal reasoning and work, rather than acknowledge them.

Kelly noted this dynamic in Rothstein’s reasons in the 2015 trilogy of landmark labour cases. “Justice Rothstein’s concurring and dissenting opinions rested on a critique in part of the majority’s political understandings of workplace power, of bargaining entitlements and tactics, and the proper roles of courts and governments,” she said. “And at the same time as Justice Rothstein criticized the majority for arguably allowing politics to trump law, the majority insisted that his reasoning was likewise influenced by a competing politics.”

She quoted Rothstein, who after retiring from the bench said, “It has long been my view that judges act with the greatest amount of legitimacy in our constitutional order where the influence of politics and personal policy preference are limited.”

She praised him as a judge who sought to maintain these limits in his own reasoning, but she insisted we need a more sophisticated discourse for analyzing when and how judges should have recourse to distributive commitments in their judicial work.

“Justice Rothstein’s immense contributions to Canadian law and legal practice suggest that our judges are well up to the task,” she said. “I think it’s high time we freed them up to do so.”

See more photos of Justice Rothstein’s book launch in our gallery.

By Jeremy Mutton