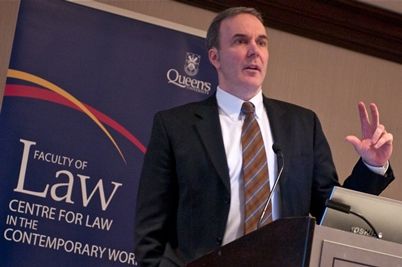

Professor Kevin Banks had the honour to chair the first ever state-to-state arbitration of an international labour law dispute and his panel released its final report this summer. The subject: a dispute between the United States and Guatemala under the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement on whether Guatemala had failed to enforce its own labour laws and whether that had affected U.S.-Guatemala trade.

The key finding: Guatemala failed to effectively enforce labour laws but the U.S. did not prove effects on trade. “The United States proved eight instances of Guatemala’s failure to effectively enforce labour laws,” explains Banks, Director of Queen’s Centre for Law in the Contemporary Workplace. “The panel had to consider whether those eight instances, or at least some of them, constituted a course of action or inaction that was in a manner effecting trade.”

“In our view, to affect trade there would at least need to be some effect on conditions of competition in trade by conferring some competitive advantage on an employer or employers,” Banks continues. “There was very little evidence pertaining to effects of the failures to enforce on union organizing or other working conditions. As a result, the panel concluded that there was insufficient basis in evidence to find that enough of the failures to enforce to constitute a course of inaction were ‘in a manner affecting trade’.”

Being the first time such a process was undertaken, it was very challenging to complete, says Banks. “First and foremost, the fact-finding process was lengthy and complex. The evidence was all in documents. The panel was required to identify and consider many possible correspondences between and inferences on the basis of what was said in the documents in order to determine whether what was alleged had in fact been proven. This was difficult and time-consuming.”

“All in all, the panel considered about 700 pages of written arguments concerning the dispute settlement process, the meaning of the law, and how it should be applied to the facts. Almost every word in Article 16.2.1 of the Agreement was the object of differing interpretations from the disputing Parties and required a reasoned interpretation from the Panel.”

Will this case provide any guidance for the upcoming NAFTA negotiations between Canada, the United States and Mexico? Banks thinks it will. “Labour issues have been an important aspect of trade agreements involving Canada or the United States for over two decades now,” he says. “NAFTA states will need to consider whether they wish to require proof of effects on trade in order to establish a violation of any labour chapter of a new NAFTA.

“That said, the causes of public skepticism about trade agreements go well beyond what can be addressed in a labour chapter,” Banks concludes. “So while the subject matter of this case is important, it is only one of many issues that governments and negotiators will have to grapple with.”

By Anthony Pugh