Jodeen Williams and Kate Dossetor, both Law’23, recently participated in the Julius Alexander Isaac Moot, a first for Queen’s Law in several years. Named for the first Black judge to sit on the Federal Court of Canada and go on to become its Chief Justice, the moot focuses on questions of racial and economic justice in law. Organized by the Black Law Students’ Association of Canada (BLSA Canada), the moot is held annually during Black History Month.

Calling it a “fantastic learning experience,” Williams says, “It was an honour and truly inspirational to present at Osgoode Hall in courts led by Black judges. Even though it was a competition, this moot had a very collegial spirit. I think that had much to do with the critical race theory lens through which the moot problem was framed. It allowed the mooters to engage in constructive debate about how the legal system and the state are failing racialized and Black populations.”

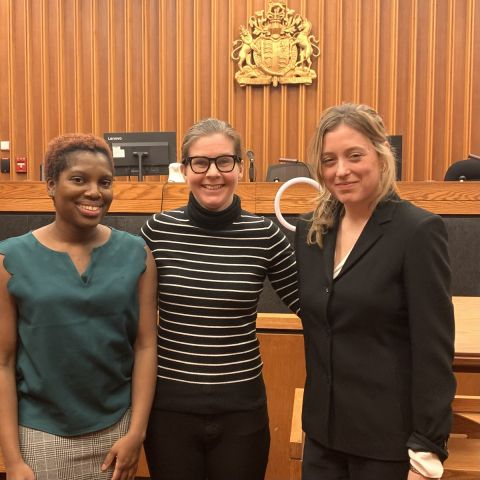

Coached by Professor Lisa Kelly, Williams and Dossetor were a respondent team in a competition of 11 law schools working on a fictional appeal of the Ontario Court of Appeal’s ruling in R. v. Morris to the Diversity High Court of Canada.

“The students worked incredibly hard on their factums and oral arguments, and this showed in the exceptional quality of their written and oral submissions,” says Kelly. “I look forward to future cohorts of Queen’s Law students participating in this important moot. It was a privilege to support Jodeen and Kate in their stellar performance this year.”

Placing equal weight on arguments rooted in doctrine and theory, Williams says, “the Isaac Moot encourages mooters to engage with themes grounded in critical race theory (CRT) when crafting their theoretical arguments. The sole doctrinal issue in this appeal was how trial judges should take evidence of anti-Black racism into account on sentencing.”

In Williams and Dossetor’s role as the Crown, it was their position that race-conscious sentencing measures should not be confused with – or distract from – transformative social, economic, and political measures necessary to combat racial injustice in the criminal system. They also argued that race-conscious measures should not overwhelm or distort the sentencing process in a way that may unwittingly aggravate the under-protection and devaluing of Black life.

The Queen’s teammates presented their arguments before judging panels of practising lawyers and the Vice-Chair of the Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services.

“I am grateful to have had this experience as this was the first time I engaged with CRT in law school,” says Williams. “CRT cannot be reduced to a single definition; it is an academic field of inquiry that both illuminates and challenges racial hierarchies in law. Critical race theorists have also expanded our thinking about how race intersects with other identities, such as sexuality, gender, class, and disability.

“The Isaac Moot,” she continues, “confronts participants with the unfortunate realities of racial inequality in our legal structures and how they may preserve the status quo and even perpetuate racial hierarchy. When faced with such realities, students are encouraged to address these issues with creativity and imagination, not only in the moot but also when we move into our respective fields of practice. In this way, the Isaac Moot, although based on a fictional appeal, has the potential to have real and lasting effects on the participants.”

Dossetor agrees. “Participating in the Isaac Moot was an incredibly rewarding experience,” she says. “It challenges students to think critically about racial inequality and anti-Black racism not only in our legal system, but in society at large. I had never engaged with critical race scholarship before, and it has had a lasting impact on me. Jodeen, Professor Kelly, and I knew it was very important to participate in this moot and to show Queen’s Law’s commitment to combatting racial injustice.”