“When I was applying to law school, I knew that the only way I could continue my education was if I was able to get financial assistance,” recalls Shelby Percival, Law’20, a proud Mohawk woman of Six Nations of the Grand River. “Coming from a separated family, estranged from my father, and with my mother taking care of my two siblings at home, money was always very tight. There was no extra money for my tuition, housing, school supplies – anything.”

A dream made possible through bursary support

She completed her Bachelor of Arts with a double major and triple minor at Wilfrid Laurier University in 2015, but wasn’t accepted to either of the Ontario law schools she applied to. Determined to improve her LSAT score, she worked three jobs to pay for a prep course. That extra effort paid off: she was accepted to Queen’s Law to begin her studies in 2017.

Knowing it would be difficult to get the grades she wanted while working part-time, she applied to every source of financial assistance available – and was ultimately awarded a bursary from the school. She went on to receive a bursary from the same fund for each of her upper years as well.

“I made the best use of the financial aid I received by keeping on a strict food budget, not buying anything extravagant or extra, and choosing to live further off campus, using my student card as a bus pass. Sometimes this meant waiting at the bus stop 30 minutes early to make sure I got to class on time. I focused on my grades and on schooling – everything else took a back burner.”

With persistence, careful budgeting, and hard work, she earned her JD – and found motivation beyond money. “In the end, it was more than just the money – it was about someone who had never met me reading my story and telling me that I was worthy to be working at becoming a lawyer – that I was valued and worthy of being an Indigenous female lawyer.”

And that is what she became. After articling at Falconers LLP in Toronto, she was hired back as an associate and continues her legal work there today.

Barriers remain for Indigenous students in law

Percival’s experience is far from unique. Financial challenges continue to limit opportunities for Indigenous students and contribute to their underrepresentation in the legal profession.

“Indigenous Peoples have historically not seen themselves represented in academic legal spaces or in the practice of law. For a long period in Canadian history, they were not considered citizens, did not have the right to vote, and could not hire lawyers,” explains Stacia Loft, Law’20, Director of Indigenous Initiatives & EDII Programs at Queen’s Law and Deputy Grand Chief of the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians. “Developing trust within the context of a systemically racist system takes time and is one of many hurdles for Indigenous learners.”

As for financial barriers to legal education, Loft says, “It is more common nowadays that Indigenous students have little to no funding for professional degree programs from their First Nation, especially if they decide to take a year off after their undergraduate degree. Many of our students decide to embark on the JD pathway with several years of professional and lived experience, including supporting their families and raising children in or close to their home communities.”

At the same time, demand for Indigenous legal perspectives has grown considerably over the years, in part due to economic growth and development. “But more intrinsically,” explains Loft, “as non-Indigenous people learn more about institutional and systemic racism, the history of the Residential School system, missing and unmarked burials and graves, missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, drinking water boil advisories, environmental impacts of industry in communities, and the historical degradation of First Nations’ inherent and treaty rights, it compels them to not only seek the truth but to also strive for justice.”

A new initiative rooted in reconciliation and representation

To achieve the dual goal of reducing financial barriers to legal education for Indigenous Peoples and increasing their representation in the legal profession, Queen’s Law has launched the Indigenous Tuition Initiative. “As part of our commitment to reconciliation, we want to offer full tuition support to Indigenous students who meet Queen’s Law’s exceptionally high admission standards,” says Dean Colleen M. Flood. “Ensuring we have Indigenous voices and perspectives represented in our classrooms strengthens not only Queen’s Law but the legal system more broadly.”

Initially, the school aims to focus on supporting students from First Nations communities located nearby, further strengthening existing relationships.

The Indigenous Tuition Initiative is one of Queen’s Law’s latest efforts to answer the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Other recent initiatives include new courses in Indigenous law and on-the-land learning, a partnership with the Kingston Native Centre and Language Nest to develop an Indigenous legal centre; a certificate program designed to help professionals across sectors build principled economic partnerships with Indigenous communities; and the appointment of Professor Kimberly Murray – the Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites – as the Queen’s National Scholar in Indigenous Legal Studies.

Learning, leading, and finding her voice at Queen’s

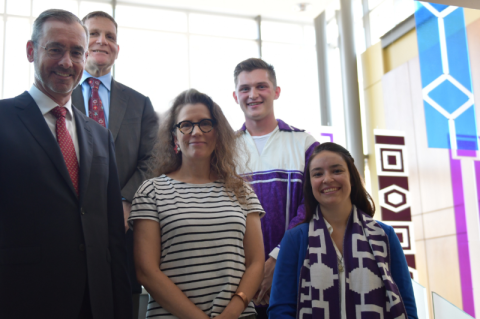

For Shelby Percival, getting involved with the school’s Indigenous Law Students’ Alliance (ILSA) and becoming a leader provided some of her most rewarding experiences as a student. She helped educate her classmates and the community about Indigenous Peoples, organized events like Orange Shirt Day, and spoke at the 2018 launch of artist Hannah Claus’s Indigenous art installation in the Law Building.

“Coming into my Indigenous heritage later on in life – since it was not something that we discussed at the dinner table in my house or even in my family, as there is a legacy of residential school harm with my ancestors – every time I had a chance at Queen’s to learn more about who I was and where I came from I took advantage,” says Percival.

Giving back through Indigenous legal advocacy

Today, she is thriving as a lawyer at Falconers LLP, where most of her clients are Indigenous and she works to advance their rights. “I do a significant amount of work with Indigenous police services across Ontario, as they work to advocate for proper funding to provide adequate and effective policing to the Indigenous communities they serve, which directly impacts Indigenous community safety.”

She is not alone in coming full circle from a first-generation university student to a practising lawyer serving her people. Indigenous JD graduates are contributing in a wide range of roles: representing First Nations in class actions, serving as Crown prosecutors or in-house counsel, drafting government policy, and leading Indigenous organizations.

“Indigenous representation in all sectors, as a practising or non-practising lawyer, matters,” says Loft. “Acts of advocacy that link directly to an Indigenous person’s or First Nation’s direct experience provide the insight necessary to achieve real and tangible outcomes to address the ongoing legacy of inequities. This is of fundamental importance to ensuring that Indigenous Peoples and our next generations are not just surviving but thriving.”

That’s why making a gift to the Indigenous Tuition Initiative matters.

Empowering the next generation of Indigenous legal advocates

“Many Indigenous students have the passion, drive, intellect and desire to go to law school to make a difference in the world that is bigger than themselves – I know that is how I was,” says Percival. “However, without financial aid, it is next to impossible for many Indigenous students to attend any level of post-secondary schooling. It’s incredibly important to reduce financial barriers for Indigenous students entering law school.”

To learn more about the Indigenous Tuition Initiative, or to make a gift, email the Queen’s Law Advancement Team at lawalum@queensu.ca.

By Lisa Graham